We’re pleased to share this interview with Anselm Winfriend Mueller, our 2017-18 visiting scholar, who is a visiting professor this quarter at the Department of Philosophy at the University of Chicago. He spoke with Johann Gudmundsson, a doctoral student at the Universität Leipzig currently on a research stay at the University of Chicago, where he’s working on his dissertation on moral judgment and practical goodness.

Johann Gudmundsson: For many years, you’ve been pursuing the thought that to act well is to act from practical reason. How are truth and goodness related to rationality? Do you think that there is a deep affinity between goodness and truth?

Anselm Winfried Mueller: Can we reasonably ask whether what you ultimately aim at in acting, rather than just whatever happens to attract you, is really good? – I think we can. At least, we take it for granted that in principle the question has an answer. For, in a year’s time, you may think you were wrong to aim at what you aimed at (much as you may come to think false what you believed to be true a year before). Such a thought makes sense only if there is a standard of goodness by which to evaluate purposes objectively (much as beliefs are evaluated objectively by the standard of truth). So ascriptions of goodness will themselves be true or false.

What is the place of rationality in this context? – To manifest knowledge, a statement has, as a rule, to be based on adequate reasons. Theoretical rationality is to this extent the way we reach truth. But a statement can be true without manifesting knowledge. By contrast, the goodness that we achieve in acting well depends unrestrictedly on what reasons we respond, and don’t respond, to. To act justly, for instance, is: to be motivated by others’ rights; to act courageously is: not to be turned away from important pursuits by the threat of danger etc.

JG: In the mid-20th century, questions relating to ethical language were in vogue, and reflection on moral discourse and meaning was held to be crucial. For example, a central question was whether ethical statements, qua speech act, should be understood as full-blown assertions or not. Those questions have faded from spotlight in recent years. How do you estimate the significance of language for ethical thought?

AWM: Quite generally, the way we talk about things supplies significant hints at their correct understanding. This is so with talk about actions and their moral qualities as much as it is with talk about causes, numbers, social institutions, or whatever.

Now, in order to improve our grasp of the relevant concepts, attention has to be directed at the interaction between the ways we talk and the ways we act. What philosophy needs to get clear about is the different roles that different uses of words play in the wider context of human social life. So philosophers have rightly become critical of arguments based simply on “what we (don’t) say”.

But, as far as I can see, present day analytical philosophy suffers more from the opposite error: its practitioners are often insensitive or indifferent to the problematic character of formulations required or admitted by their theories, when by taking notice of it they might have discovered, e.g., that the phenomena they were hoping to cover by a unifying account were in fact more disparate than this account allowed.

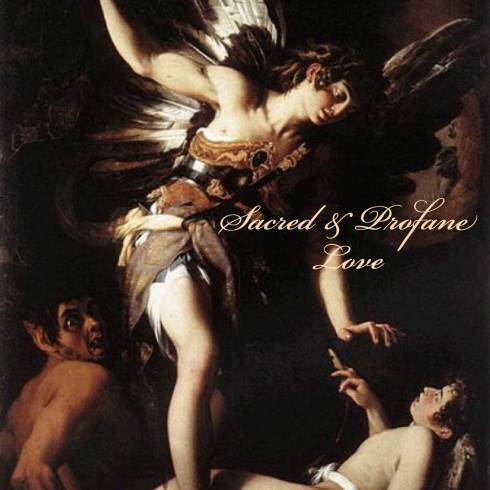

JG: It seems that there are two kinds of good that pertain to human beings. On the one hand, there’s individual well-being or happiness. On the other hand, there’s moral perfection. Would you be happy to draw this distinction? If yes, how do you think individual happiness and moral perfection are related?

AWM: I can’t say that I would be happy to draw that distinction. Shouldn’t one feel honored to belong to a species noble enough to find their happiness guaranteed by adherence to reason realized in a life of virtue, as the Stoics taught?

Unfortunately, this doctrine is a sort of philosophical self-deception. It is indeed true, I think, that a person cannot be happy without attempting to lead a virtuous life. And also, that human happiness cannot but consist in the satisfying use of reason. But we just have to acknowledge that serious suffering tends to prevent the virtuous person from being happy.

Moreover, although the practice of virtue is typically a source of happiness, there are other things as well, such as family life or the successful pursuit of a worthwhile project, that may well be constitutive of the (limited) happiness a man is able to attain. I agree that it won’t make you happy to pursue such a project by evil means. But this does not mean that ethical virtue is the feature of your pursuit that secures your happiness.

So honesty requires us to answer your first question by acknowledging the distinction between happiness and moral perfection. The second question may be one of those that it is the task of philosophy to raise and keep alive although it cannot answer them. As Kant observed, we just cannot discard the idea that there “must” be a way in which the pursuit of virtue issues in happiness. This, too, honesty requires us to recognize. I suspect it is even part of virtue itself to think, with Socrates: It cannot, ultimately, be to my disadvantage to pursue it.

JG: You probably would agree that the aim of philosophical activity is to get clear on certain fundamental notions. The aim of practical philosophy then would be to clarify notions such as intention, reason, goodness and rationality. Do you think that practical philosophy can also be of practical guidance by providing answers to substantial moral questions? Or can such answers only be reached beyond philosophy, for example in public discourse, individual conscience or religious traditions?

AWM: It would be pleasant for practical philosophers to think of themselves as benefiting humanity by giving the kind of guidance you mention. But I think their ambitions have to be more modest.

I am not a skeptic about the possibility of showing that human life is in need of moral norms. But, first, such demonstrations remain theoretical: they explain moral requirements, and they give you reason to believe that doing this and avoiding that serves human flourishing; but they do not thereby already give you reason to do this and avoid that. And, second, nobody – philosopher or not – will adopt a moral norm such as: not to cheat, or: to take responsibility for one’s children, or: to refrain from cruelty, because of a philosophical demonstration; for one’s conviction of the need to comply with such norms will almost certainly be more certain than one’s confidence in any philosophical argument for them.

Nevertheless, philosophers need not despair of their public utility. On the one hand, people who already listen to the voice of virtue are in a position, and will be ready, also to learn, for their practice, from theoretical reflexion on what you call substantial moral questions – on how to carry on in view of considerations that may have escaped them. On the other hand, and possibly even more importantly, good philosophy is needed to refute the brand of bad philosophy that claims to show that morality is an illusion, or that what it enjoins is “authenticity” in the pursuit of your likings, or the like – the kind of claim that is sensational or shocking enough to make it into the media and is hailed by those already tempted to deceive themselves, or compromise, where moral requirements challenge their questionable inclinations.

I am not myself enough of a columnist to take on the task of facing popular versions of misguided philosophical claims. The job that your question well describes as clarifying “notions such as intention, reason, goodness and rationality” is (I hope!) more congenial to my temperament and talent. So I cheerfully resign myself to peaceful exchange with those enviable colleagues who engage in both “philosophizing for philosophers” and “philosophizing for the world”.

Johann Gudmundsson got his Magister Artium degree in Philosophy and German studies from the Universität Leipzig after having studied there and at the University of Iceland in Reykjavik. He then worked as a research assistant at the Universität Leipzig and as a coordinator of a project funded by the National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina on institutional and quality problems of the German doctorate, and now a doctoral student at the Universität Leipzig currently on a research stay at the University of Chicago, where he’s working on his dissertation on moral judgment and practical goodness.

![]() Subscribe

Subscribe

This post is an excerpt of “Living Within Reason” on the blog “Virtue Insight”, of the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtue, available here.

This post is an excerpt of “Living Within Reason” on the blog “Virtue Insight”, of the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtue, available here.

Candace Vogler is the David B. and Clara E. Stern Professor of Philosophy and Professor in the College at the University of Chicago. She has authored two books, John Stuart Mill’s Deliberative Landscape: An essay in moral psychology (Routledge, 2001) and Reasonably Vicious (Harvard University Press, 2002), and essays in ethics, social and political philosophy, philosophy and literature, cinema, psychoanalysis, gender studies, sexuality studies, and other areas. Her research interests are in practical philosophy (particularly the strand of work in moral philosophy indebted to Elizabeth Anscombe), practical reason, Kant’s ethics, Marx, and neo-Aristotelian naturalism. She is the co-Principal Investigator for the project Virtue, Happiness, & the Meaning of Life.

Candace Vogler is the David B. and Clara E. Stern Professor of Philosophy and Professor in the College at the University of Chicago. She has authored two books, John Stuart Mill’s Deliberative Landscape: An essay in moral psychology (Routledge, 2001) and Reasonably Vicious (Harvard University Press, 2002), and essays in ethics, social and political philosophy, philosophy and literature, cinema, psychoanalysis, gender studies, sexuality studies, and other areas. Her research interests are in practical philosophy (particularly the strand of work in moral philosophy indebted to Elizabeth Anscombe), practical reason, Kant’s ethics, Marx, and neo-Aristotelian naturalism. She is the co-Principal Investigator for the project Virtue, Happiness, & the Meaning of Life.