“In keeping silent about evil, in burying it so deep within us that no sign of it appears on the surface, we are implanting it, and it will rise up a thousand fold in the future. When we neither punish nor reproach evildoers, we are not simply protecting their trivial old age, we are thereby ripping the foundations of justice from new generations.”

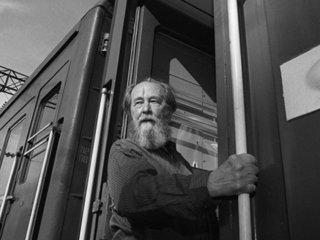

So wrote Nobel Prize-winning Russian novelist Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn in his monumental The Gulag Archipelago, detailing the history and horrors of the Soviet labor camps, published 43 years ago this week. The book was met with instant international acclaim; one review in the New York Times called its subject “the other great holocaust of our century.” In the wake of its publication Solzhenitsyn became something of a pop-culture cold war hero in the U.S., where interest in militarism and interventionist policies had been fading in the aftermath of Vietnam. Solzenitsyn’s belief that Russia should turn away from international military involvement and embrace the Church and its own rich cultural history was favorably received by conservatives, as was his view that the U.S. had capitulated too quickly in Vietnam. Liberals embraced him as a dissident and rebel, though he was criticized for his insistence that Lenin was as culpable as Stalin for the monstrous atrocities of Soviet totalitarianism, and that the political state is often its own end regardless of its founding ideology.

Solzhenitsyn’s unstinting criticism of Western materialism often made him a difficult figure. He spent nearly two decades in the U.S., yet never stopped railing against what he saw as its moral complacency and spiritual emptiness. In 1978 he shocked many with his commencement address at Harvard University, where he was given an honorary doctorate in literature. In it, he urged his audience to look beyond the material satisfactions of U.S. culture:

“If humanism were right in declaring that man is born only to be happy, he would not be born to die. Since his body is doomed to die, his task on earth evidently must be of a more spiritual nature. It cannot be unrestrained enjoyment of everyday life. It cannot be the search for the best ways to obtain material goods and then cheerfully get the most of them. It has to be the fulfillment of a permanent, earnest duty so that one’s life journey may become an experience of moral growth, so that one may leave life a better human being than one started it. It is imperative to review the table of widespread human values. Its present incorrectness is astounding. It is not possible that assessment of the President’s performance be reduced to the question how much money one makes or of unlimited availability of gasoline. Only voluntary, inspired self-restraint can raise man above the world stream of materialism.” Link

Critics often shrugged off Solzhenitsyn’s social commentary while acknowledging the truth of the horrors he wrote about; one anecdote in his New York Times obituary recounts Susan Sontag’s conversation with Russian poet Joseph Brodsky:

“We were laughing and agreeing about how we thought Solzhenitsyn’s views on the United States, his criticism of the press, and all the rest were deeply wrong, and on and on,” she said. “And then Joseph said: But you know, Susan, everything Solzhenitsyn says about the Soviet Union is true. Really, all those numbers—60 million victims—it’s all true.”

Also included in the Times obituary is the story of how Solzhenitsyn managed to smuggle out writing under the harshest conditions of Soviet internment. Banished under Stalin to Ekibastuz, a camp where writing was routinely confiscated and which would become the source of his novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch, Solzhenistyn used a special rosary fashioned for him by Lithuanian Catholic prisoners to commit 12,000 lines of prose to memory, using one bead for each passage.

Such conditions are almost impossible to fathom for Americans living today in a world of relative material comforts and freedom of the press. Yet his critique of our shallow moral standards and sense of entitlement is at least as relevant now as it was in 1978. Should we elect political leaders based on our satisfaction or dissatisfaction with our salaries, or the price of gas? Or should we also have a higher purpose in mind, a vision of somehow making the world a better place?

Solzhenitsyn was prescient about the effect materialism would have on the political landscape, seeming to forecast the yearning for what Ronald Reagan would articulate a couple years later as “morning in America,” the vision that rejected the economic and political uncertainty of the Carter years in favor of a nation characterized by plentiful goods, free enterprise, and military might. Now it appears we are in another 1978 moment, a moment characterized much as it was then, by economic fear, fear of international terrorism, and lack of faith in political leadership. In The Unfinished Presidency: Jimmy Carter’s Journey Beyond the White House, Douglas Brinkley describes the moment of Carter’s loss as one that seems on the surface very unlike our own, yet at bottom contains the same underlying fear and malaise. Carter’s era culminated in “inflation in the double digits, oil prices triple what they had been, unemployment above 7 percent, interest rates topping 20 percent, fifty-two American hostages still held captive in Iran, and unsettling memories of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.” Link

In contrast, the U.S. economy this October, just before the 2016 election, saw the biggest economic growth in two years, increased exports, and a shrinking unemployment rate, yet the economic insecurity of 2008 continues to linger eight years later, much as the effects of recession lingered throughout the 1970s. U.S. growth in October of this year was historically slow compared to historic measures, and our “gig economy,” where people drive their own cars for companies like Uber and Lyft, means that millions of workers are filling temp jobs because they can’t find stable, well-paying work. Link

Thus while we are not nearly as precarious economically as we were in 1980, we feel as precarious as we did in 1980. On the one hand, it is right to take note of economic conditions that leave too many people living in poverty, whether from the unavailability of any work or the availability of only the lowest-paying kind of work, and as a result choose to vote for better opportunities for everyone. On the other hand, faced with having too little, or thinking we have less than we should, or fearing we will lose what we have, some of us vote to have more, no matter the cost.

We find it hard to ask, whether in asking for more than we have, or more than we think we can get, if we are in fact asking for the right things. In the wake of a 2016 election defined for many by the fear of “falling behind,” of losing the material security promised by the American Dream, we need to think about how we define the contents of that dream and examine the entitlement behind the notion of “falling behind.” We now know that many more voters were galvanized this year by appeals to fear and entitlement than were moved by visions of social justice and equality. We need to address the appeal of fear and entitlement before we can go on to articulate a larger vision of a just society where there is opportunity for everyone.

Appeals to morality rarely win elections. We now know that “the unlimited availability of gasoline,” for example, while making certain economic sense, is not the best thing to ask for when electing public officials, especially given the devastating effects of carbon emissions on the global environment. Yet the virtue of self-restraint—temperance, really—called for by Solzhenitsyn in his Harvard commencement address is no more popular now than it was in 1978, when many Americans rejected it in favor of a 1950s-style domestic prosperity characterized by plenty of cheap gas and consumer goods.

President Carter, a famously moral person who spoke openly against violence and advocated daily prayer, was unable to effectively sell his vision that U.S. voters should cultivate temperate, self-transcendent characters. Solzhenitsyn’s warning in this era that human life must consist of more than “the search for the best ways to obtain material goods” vanished in a country weary of recession and fearful of international terrorism, and is similarly lost today in a nation where people fear slipping into poverty at home as a result of stagnant wages and vanishing jobs, and see only an unstable and violent world abroad. Yet Solzhenitsyn’s warning that Americans—humans—are prone to self-interest and self-indulgence is one we should still heed. His insistence that the human tendency to keep one’s head down in the presence of injustice proliferates injustice is especially urgent in our moment, when the temptation to retreat into private life can seem so seductive. In this dangerous world, getting involved is a necessary self-transcendence, “the fulfillment of a permanent, earnest duty,” a call to witness, and a call to action.

Jaime Hovey is Associate Program Director for Virtue, Happiness, & the Meaning of Life.