Introduction

A basic Aristotelian insight taken up and developed by Thomas Aquinas is that animals tend to move toward what is good for animals of their kind, and to avoid things that are bad for their sort of animal. Aquinas recognized that, among animals, things are uniquely hard for human beings—the intellectual animals. We get in the way of ourselves, even when we are fully grown and of relatively sound mind and body. We get in our own way even when we are, as one says, highly functional. Aquinas understands that even the best of us will have good reason to regret some of what we do or fail to do, say or fail to say, think or fail to think. This is part of the burden and glory that comes of being the kind of animal that is accountable for a lot of what it does voluntarily, and that needs to figure out what to pursue and why. It is difficult to manage self-direction in circumstances where even the most basic things about our lives seem increasingly to be matters of choice and it takes us a few years to so much as reliably to distinguish what is edible from what is inedible. And humans are not just in danger of inefficiency or disappointment in their efforts to move toward what draws them, and avoid what they find repugnant. They are at moral risk. As medieval English poets used to notice, when the wolf is drawn to a thing, that thing will tend to be a good sort of thing for a wolf to seek. When a man is drawn toward something, it could be morally disastrous.

Under these circumstances, young people I have known routinely move around difficult moral questions using the language of etiquette. They are worried about imposing on others. They don’t know how even to begin a discussion about topics that involve vital aspects of people’s lives—often aspects that seem at once crucial, emotionally charged, and intimate. Sometimes they genuinely do not know how to begin thinking their way into a question.

I should note at the outset that rational enquiry into different understandings of good and bad in human life does not constitute an imposition, even if what it reveals is profound disagreement on some points. It does not constitute failing to respect others. If anything, thoughtful disagreement shows serious regard for one’s opponents. And, when it comes to coping with a moral dispute, relying on the traditional point about good and bad can help.

It could be that people who occupy different positions across a vast divide are disagreeing about human good at every level. I suspect that this is very rare these days. That we need food, clothing, clean water, clean air, security in our persons, some form of community, something that counts as family, some reliable economic institutions, some measures of freedom of worship, assembly, and expression—that these kinds of things are good for intellectual social animals is usually a shared understanding among contemporary humans. It is hard to imagine serious, reasoned disagreement on such matters. But significant background agreement on these points will not be enough to settle all questions. It is not even enough to settle all questions in personal life, much less in matters of public policy, and human life, lived in the varying contexts of human institutions, is often muddled, homely, and disappointing.

For all that, I suspect that when we find ourselves at odds with others over some moral question we will find substantial agreement about human good in general across the many divides that look to make consensus impossible. In my limited experience, it helps to begin by acknowledging that more than one sort of good is at stake in moral disagreement, and to take seriously the genuine good or goods at issue in a dispute. Where those goods are concerned, all of us will tend to be moral realists.

What are we Being Realists About?

How much realism do we get from the kinds of points that people are taking for granted in thinking that things have been bad in Puerto Rico since Hurricane Maria made landfall? That having access to food, water, fuel, electricity, and stable shelter would improve life for the people there? We are tacitly committed to there being such a thing as human nature, to a recognition that humans are vulnerable creatures, to an indeterminate number of claims about the badness of the situation for human beings on an island in the wake of a catastrophic hurricane.

We know these things.

This is not a matter of ungrounded opinion. Our inferences about the situation in Puerto Rico are not beholden to some sort of standard of rational justification that is relative to the cultural markings that we carry in virtue of belonging to this or that community. Most people in Puerto Rico are struggling to deal with flooding and the like, but we are on solid ground as far as our sense that things have gone badly for them is concerned.

As I say, this kind of baseline is rarely enough to make much headway with difficult moral questions, but it is the sort of thing that does provide common ground across many deep divides. Objective common ground. Moral truth.

What of the Difficult Questions? What About Relativism?

But, given that most of the moral matters that tear at us involve questions much more difficult than a question about whether victims of natural or manmade disasters have gone through something bad, how much comfort can we take in having unspoken, shared commitments of the sort that surface whenever anything terrible happens? What of moral relativism, that specter that threatens to materialize in ordinary undergraduate classrooms at the drop of a hat in introductory ethics courses?

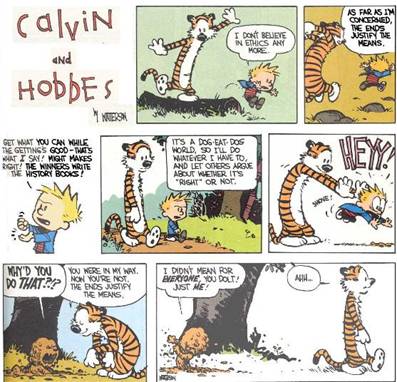

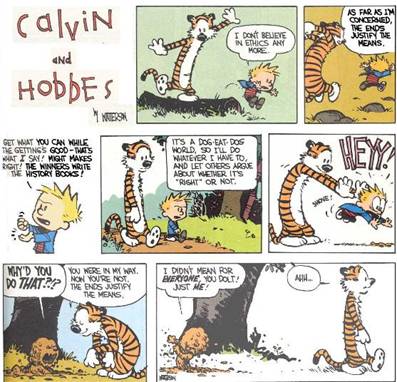

The most extreme form of moral relativism is moral subjectivism—the topic of the cartoons on this page. This view—that claims to moral truth are merely subjective—lapses into incoherence as quickly as the cartoons suggest. There are two other forms of moral relativism that have more bite.

Descriptive moral relativism centers on the claim that different cultural groups adhere to different moral codes, frequently embodied in different practices, different standards of justification, different kinship systems, different modes of work and leisure, and different customs, and normally systematically linked to members’ consciences. This form of relativism has the advantage of being very likely true. There are significant divergences in moral codes across diverse human communities. If the first thing to notice about descriptive moral relativism is that it may well be true, the second thing to note is that its truth will not have any effect on moral disagreement. For example, it says nothing about the relative soundness of the moral codes that diverge. It could be that some of those codes are better than others. It may be that some are true and others are false. To notice differences is not to say what we should make of those differences.

Normative moral relativism claims that not only will we find the kinds of divergence that the descriptive relativists highlight, but we ought to see divergence in moral codes in different societies. Does normative moral relativism have any bearing on the possibility of coping with serious moral disagreement? It will depend upon how the normative relativist fleshes out the suggestion that moral codes ought to diverge. For example, one persistent site of significant moral divergence enters in through historical distance. Even those of us who have come to love the Iliad or the Odyssey—to name two canonical European great books—will likely notice that the moral codes that seem to inform the Homeric epics diverge significantly from the codes we came to inhabit in our childhoods. If the normative relativist explains this by talking about the dramatically different situations we find ourselves in now, and the social, material, and political worlds that form a kind of backdrop and context for ancient Greek warrior poetry, then the divergence may, to the extent that we can comprehend the differences, begin to feel like the sort of thing that is to be expected of human beings facing these different worldly circumstances. The pressures on that (likely partly imaginary) civilization, the resources available, the modes of human connection and antagonism that were taken for granted in the poetry were so far removed from ours that the differences make sense. This sort of observation is one form that normative moral relativism can take. Again, it says nothing about our prospects for handling deep contemporary moral disagreement, except to suggest that we might do well to develop an imagination for the pressures that those who disagree with us face, and the resources that they have at their disposal for finding ways of pursuing collective goods, and avoiding bad, in their communities before declaring them utterly benighted.

The View from one Philosopher’s Seat

Alasdair MacIntyre—a contemporary Anglophone philosopher broadly concerned with ethics—has circled around the topics of relativism and cultural difference for many years. He has written thoughtfully and well about communities, about the cultural contexts communities provide for moral development, about character, and about the peculiarly shrill tone of contemporary moral disagreement. In an essay called “Moral Relativism, Truth and Justification”—there are long quotations from it on your handout—he takes up the topic of seemingly intractable moral dispute, linking disagreement to cultural difference. He begins with an example taken from a 17th century Japanese Neo-Confucian called Kaibara Ekken. Ekken argues that a man has sufficient grounds to divorce his wife if she is disobedient to her in-laws, if she gossips or slanders others, if she is barren or jealous, if she has a serious illness, and so on. Ekken defends the view by pointing to role a wife was meant to play in society, to the structure of family life, to the place of that structure in the larger moral and political order, and to the cosmic order in which these institutional arrangements had their proper places.

MacIntyre turns next to the natural law tradition in European thought, grounded in Stoicism and Roman law and given significant development in medieval philosophy—most notably in the work of Aquinas. MacIntyre points out that Aquinas does not see a wife’s fondness for gossip or friction with her in-laws as grounds for divorce, nor would Aquinas find a sound argument for divorce if she became ill or was barren.

Neither view, MacIntyre points out, seems to have the kinds of resources that would be needed to make its case in terms that the other view would accept. Each position can be defended in its own terms. But it looks like the gulf between the two views cannot be bridged by an argument that relies upon the modes of justification internal to either protagonist’s cultural milieu. The prospects for Aquinas and Ekken settling their imagined dispute look dim, MacIntyre thinks.

Nevertheless, both sorts of view present themselves as true. Neither of these two thinkers is a relativist. How, then, are we to square the universalist claim at the root of each position with the difficulty in even imagining how Ekken and Aquinas might have a meeting of minds on the question of divorce?

MacIntyre goes at the question through a serious discussion of the nature of substantive views of truth—the only sorts of views of truth that he takes to be compatible with the tenor and tone of serious moral divergence. It is a good discussion, and forms the basis of an almost uncharacteristically optimistic account of how we might handle ourselves in the face of seemingly intractable moral disputes. At least, that is one way to read the essay. One could also read it as a reduction.

Having insisted—and he is surely right about this—that the protagonists to a serious moral dispute must be seen as claiming truth for their positions, MacIntyre outlines three things that follow from the understanding that they are claiming to be teaching us moral truths:

First, they are committed to holding that the account of morality which they give does not itself, at least in its central contentions, suffer from the limitations, partialities, and one-sidedness of a merely local point of view, while any rival and incompatible account must suffer to some significant extent from such limitations, partiality, and one-sidedness. Only if this is the case are they entitled to assert that their account is one of how things are, rather than merely how they appear to be from some particular standpoint or in one particular perspective….

Secondly, such protagonists are thereby also committed to holding that, if the scheme and mode of justification of some rival moral standpoint supports a conclusion incompatible with any central thesis of their account, then that scheme must be defective in some important way and capable of being replaced by some rationally superior scheme and mode of justification, which would not support any such conclusion.

Thirdly and correspondingly, they are committed to holding that if the scheme and mode of justification to which they at present appeal to support the conclusions which constitute their own account of the moral life were to turn out to be, as a result of further enquiry, incapable of providing the resources for exhibiting its argumentative superiority to such a rival, then it must be capable of being replaced by some scheme and mode of justification which does possess the resources both for providing adequate rational support for their account and for exhibiting its rational superiority to any scheme and mode of justification which supports conclusions incompatible with central theses of that account.

To make good on our convictions, he argues, we need to be committed to serious rational inquiry. It will require both philosophical skill and a strong imagination to transcend those aspects of our own views that are one-sided, provincial, and otherwise stained with the local color that characterizes our position. It is not impossible to do this, he suggests. It is just very difficult, and it can only be done with the understanding that we may need to alter our own views in light of what rational enquiry reveals to us about our position.

Two Cautionary Notes from the Sideline

I am a great admirer of MacIntyre’s work, but want to suggest that this discussion of relativism and its possible remedy suffers from two sorts of exaggeration. First, even though MacIntyre stresses the importance of open-mindedness and imagination in his account of how rational enquiry might help us to remedy our situation, I think that he overestimates the power of rational enquiry. It may be an occupational hazard for philosophers. I sometimes think that some of the best of us got into this business because we were hunting for the good argument that could stop manmade bad things from happening—the line of thinking that could settle disputes in our families, or put political strife to rest, or bring about peace and harmony in social life if only people would listen. I don’t know MacIntyre well enough to have any view about his motivations on this score, but a lot of us who lived by our wits in youth hoped to make the world better by our wits as adults. It could be that we need more than solitary acts of brilliant thought and imagination to sort out a real ethical tangle. We might need more than collective acts of brilliance, even. Some of the ground underlying central moral convictions may exceed the limits of even the splendid, repeated, enduring collaborative exercise of our intellectual powers and strengths. Aquinas seems to have thought so. The very first article of the very first question of first part of the Summa Theologiae, for example, urges that we need revealed knowledge to help us answer central questions about how we ought to live, that philosophy alone—by which he likely meant Aristotelian metaphysics—was not enough. He was, himself, an enormously good philosopher with extraordinary powers of methodical rational enquiry and a vast and fertile imagination. If he couldn’t do it, it is hard to see why we would expect to succeed. I tend to think that accepting his counsel on this point is a good idea.

The standards MacIntyre provides for guiding our enquiry are clear analytic philosophical standards. They are good standards. But they may demand more of us than moral thought and practice can provide. Why would one think that the kinds of intellectual standards that are the air we breathe in analytic philosophy are the ones that will help us when faced with deep moral disagreement?

This question brings me to the second place where I think that MacIntyre is inclined to exaggerate. He has taught us all a lot about the kinds of unity we can find embodied in the people and practices that mark out distinctive moral communities. And it is likely that some of his acuity in these matters owes a lot to his youthful adherence to some form of Marxism—again, I do not know him well enough to know which Marxism (or Marxisms) shaped his youthful social and political activism. I don’t know if he read work by Antonio Gramsci or Louis Althusser, by Lenin or Rosa Luxemburg or Mao. All of these activist thinkers found themselves coping with the fact that, contrary to what they might have expected, European wage laborers did not rise up to throw off their chains. Worse, in the parts of the world where there were uprisings in the name of Marx, the people who rose up were not wage laborers, suggesting that the whole mode of thinking about class and class conflict that was not quite theorized by Marx—but was strongly suggested by his work—was somehow not quite right. All of these thinkers, in different ways and with different emphases, urged that neither culture nor class interest was as singular or coherent as Marx seemed to have thought that it could be. The social fabric, they claimed, was not a tightly woven bolt of cloth with a single seam that could be ripped out if only the masses could collectively recognize their interests. Instead, the social fabric was a loosely woven, shifting, unevenly fraying thing that did not provide a single, coherent social script for anyone.

I have found some of this work very useful. When MacIntyre writes about the wonderful community spirit in a remote small fishing village, or the way that ancient Greek thought about virtue had its natural home in the life of the polis, or even of the systematic coherence and wholeness of Ekken’s Neo-Confucian thought about marriage and divorce, to my jaded eye, at least, he has a tendency to see the weave of the relevant social fabric as tighter than social fabric tends to be. Now if cultures provided something more like scripts and less like patchy, fraying collective contexts in which people seek ways of pursuing common good and addressing human needs and inclinations, then the analytic philosophical demands on standards of reason and argument would look more appropriate. In dealing with disagreement, we would be trying to cope with a clash between divergent systems that came wrapped up in whole modes of rational justification that may or may not be of a kind that we can match. Our task might look like the moral equivalent of trying to express Newton’s laws in the terms characteristic of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. It is very hard to do, but with sufficient mathematical skill and imagination, it can be done without too great a loss of content. If, however, like much of human life, moral thought and moral disagreement is a messy business carried out at the edges of ways of thinking that are in some ways underdeveloped and in many respects provisional, then it will look as though MacIntyre is not fully heeding Aristotle’s advice. He is looking for something more determinate than what we have a right to expect in ethics.

The ways in which the views in the background of moral disagreement will tend to be less than fully developed and other than entirely logically systematic, however, provides us with real possibilities for moral engagement from that mundane kind of ground we have in our recognition that our opponents are fellow human beings who are working to pursue good and avoid bad. We are, all of us, doing that. All of us will fail sometimes. All of us can use disagreement as a way of developing a better sense for both diverse human efforts to move toward good and the ways in which we can learn from each other’s successes and mistakes. MacIntyre is dead right, I think, to urge that we approach moral disagreement with humility, honesty, and a willingness to engage in self-criticism at least as strong as our willingness to find fault with others.

Candace Vogler is the David B. and Clara E. Stern Professor of Philosophy and Professor in the College at the University of Chicago, and Principal Investigator for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life. Vogler gave this talk at Vanderbilt University October 5, hosted by the Thomistic Institute chapter in Nashville.

Michael Gorman, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Catholic University of America is the author of Aquinas on the Metaphysics of the Hypostatic Union, June 2017, Cambridge University Press.

Michael Gorman, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Catholic University of America is the author of Aquinas on the Metaphysics of the Hypostatic Union, June 2017, Cambridge University Press.

Owen Flanagan, James B. Duke Professor of Philosophy and Professor of Neurobiology at Duke University is the author of The Geography of Morals: Varieties of Moral Possibility, Oxford University Press, 2017 and co-editor of The Moral Psychology of Anger, forthcoming from Rowman and Littlefield.

Owen Flanagan, James B. Duke Professor of Philosophy and Professor of Neurobiology at Duke University is the author of The Geography of Morals: Varieties of Moral Possibility, Oxford University Press, 2017 and co-editor of The Moral Psychology of Anger, forthcoming from Rowman and Littlefield.