This post was written after a visit to ArtAIDSAmerica Chicago, at the Alphawood Gallery, 2014 North Halsted Street, Chicago. The show runs through April 2, 2017.

It is hard to enter the space of the ArtAIDSAmerica Chicago exhibit without experiencing outrage. The massive human tragedy caused by years of governmental and mainstream social indifference toward a disease that wiped out an entire generation of young men here and abroad, as well as women and children, and that still rages on today, draws comparison to the callous use of soldiers as machine gun fodder by the decrepit British generals of the First World War, or the stubborn insistence by the Johnson and Nixon administrations that teenaged boys by the truckload be shipped off to die in Vietnam. In 1980, 31 people had died of what would later come to be known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. Ten years later, the death toll in the U.S. alone was 18,447, and continued to rise throughout the 1990s. People living with and dying of AIDS included all sorts of people–gay men, male and female IV needle users, straight and gay women, hemophiliacs, and children born to HIV-positive mothers. Still, the disease was perceived as particular to gay men, and as a result of the stigma associated with them, the U.S. government failed to respond quickly to the crisis.

Artists responded to the crisis by making overtly activist and political art. Many works in this show foreground issues of exclusion, stigma, and injustice. Entering the exhibit, one is immediately confronted by Nayland Black’s 1991 “Every 12 Minutes,” a clock on the wall with STOP IT! written in the middle, its face divided into 5 equal sections by the words “ONE AIDS DEATH.” The clock exhorts us to stop these deaths, but it also commands us to stop all the other behaviors contributing to the crisis, from spreading misinformation to having unsafe sex to stigmatizing people with the disease.

Turning from the clock, visitors can see a shimmering bluish beaded curtain by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Water), 1995, that stretches across a wide entryway, separating the entryway from the room beyond. Yet through the clear and bluish beads this next room is also gauzily visible, glowing and beckoning from beyond a veil.

In a small, adjacent room Native American symbols speak to both stigma and loss. David Wojnarowicz’s gelatin silver print “Untitled” (Buffalo), 1988-89 is a photograph of a diorama of the Native American hunting practice of herding buffalo off a cliff, suggesting the intentional killing of people with AIDS not only through indifference, but through active hostility and homophobia. Ronald Lockett’s “Facing Extinction,” 1994, made of chalk, metal, and wood, shows a ghostly buffalo, a recurring symbol for Lockett of hunted creatures. It stands on a too-solid three-dimensional cliff, gazing into our space as its body begins to disappear into the background. “More Time Expected,” 2002, by Sicangu Lakota artist Thomas Haukaas, shows figures riding singly and in pairs surrounding a riderless horse, symbolizing those felled by the disease.

“More Time Expected,” 2002. Thomas Haukaas. Photo by Jaime Hovey.

Part Gonzalez-Torres’s beaded glass curtain and enter a large open space with soaring ceilings. On one wall, a recreation of ACT-UP NY/Gran Fury’s 1987 video and neon installation “Let the Record Show” shines like a dark window, dominating the room. At the top a neon pink triangle glows steadily over white letters spelling out the famous ACT-UP logo, “Silence = Death.” The projection of an arched crescent and decorative columns around the outside of the logo gives it an architectural quality, like a temple or a church nave, beneath which long panels stretch down like stained-glass. Here photographs of six people from the Reagan era are superimposed on an old photograph of the Nuremburg Trials depicting Nazi war criminals seated in a courtroom guarded by Allied soldiers. An electronic panel with running titles in red shows AIDS statistics and epidemic facts. The superimposed photographs light up and go dark, alternately revealing the faces of Senator Jessie Helms, columnist William F. Buckley Jr., Cory Servaas of the Presidential AIDS Commission, an anonymous surgeon, and President Ronald Reagan. These are the war criminals of the AIDS crisis. Underneath each face is an offensive quote made by each one about disease victims, such as Buckley’s infamous assertion that people with AIDS should be “tattooed on the upper forearm, to protect common-needle users, and on the buttocks, to prevent the victimization of other homosexuals,” or the surgeon’s quip that AIDS provided a better reason to “hate faggots.” To underscore the work’s declaration that silence equals death, there is no quote from Reagan, who famously said nothing even as the worst health epidemic in centuries raged around him.

Other mixed-media and video works include a bank of screens with headphones and seating for projects such as T. Kim Trang Tran’s “kore,” 1994, which swoops in and away from grainy black and white moving images of Asian men relaxing at the beach or walking through cities, zooming out every so often to show these figures, distanced from us by time, being watched by other men and boys on hand-held screens and scrolls. The gaze created here suggests that cruising after AIDS cannot be dispassionate; the look of curiosity, appreciation, and desire for Asian men created in and by these images is now tinged with melancholy, memory, and loss.

Still from “kore,” 1994. T. Kim Trang Tran. Photo by Jaime Hovey

In what is thought to be the first AIDS painting, Izhar Patkin creates in his “Unveiling of a Modern Chastity” a surface of erupting skin lesions fashioned out of rubber paste, latex, and ink. Moved by the symptoms he saw in patients at his dermatology office, he documented their wounds a year before there was any public announcement about the disease or its victims. Here the sores break open the skin of the painting to ooze and glisten in the light, pushing through from underneath as if something monstrous is housed inside. The painting is shocking, but it also forces the viewer to confront the disease at the level of skin, pain, and the body.

The cumulative effect of these works is to move viewers from outrage at homophobic and indifferent responses to the epidemic to admiration at the courage and resilience of AIDS artists, activists, allies, and survivors. In these works we see creative, political, and deeply moral reactions to the absence of justice, to the withholding of compassion, and to the celebration of love in America at a time when huge numbers of people were suffering and dying.

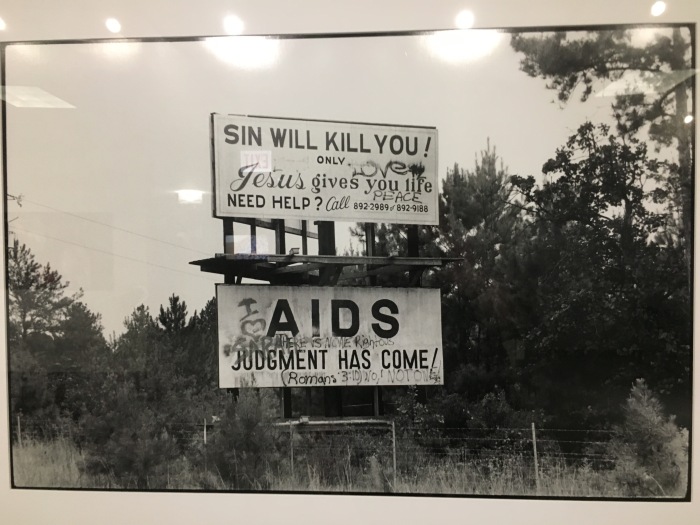

Religious imagery shapes many of the works, speaking to the gulf between the moral response of the queer community–which involved projects such as public safe sex education and meals on wheels for the homebound–and the judgmental condemnation and indifference of government officials and mainstream religious groups, which shuttered bathhouses and gay clubs in a misguided effort to stop gay sex from happening. In “AIDS—JUDGMENT HAS COME, Slidell, Louisiana,” Ann P. Meredith documents a set of billboards she saw in Louisiana as she traveled to photograph women living with AIDS. Her print shows the harsh messages of the billboards as undercut by a graffiti tagger who writes “Love” and “Peace,” and slyly quotes from Romans 3:10, “There is none righteous, no, not one,” a verse that when it appears in the Bible is followed by the words, “There is none that understandeth, there is none that seeketh after God.”

Keith Haring’s gleaming silver “Altar Piece,” the last work he completed before he died, shows a weeping Mary with a shining heart and multiple arms holding the infant Jesus under a cross in the center panel of a triptych. Here the Trinity is reimagined to include her, and below her crowds raise their hands in anger and supplication as angels fly and fall.

Echoing the theme of Icarian angels, Daniel Goldstein’s “Icarian I Incline,” fashions a Shroud of Turin from the leather cover of a weight bench that once belonged to the Castro gym Muscle System, nicknamed Muscle Sisters by patrons. Stained with the sweat of a thousand gay men, many of whom have since died, the cover bears the ghostly image of their bodies, framed here as a relic memorializing the exuberant communities that flew too close to the sun, flourished before AIDS, and came together to support each other during and after the crisis.

Martin Wong’s 1988 “I.C.U.” shows an eye in a triangle floating over a brick building. Echoing the pink triangle in the nearby “Let the Record Show,” the eye above the building here resembles the eye on a dollar bill, but appears amidst constellations, like the eye of God. A pun on “I see you,” the letters are also the common abbreviation for Intensive Care Unit, the place in hospitals where so many gay men lay dying during the epidemic. In this work, most of the brick building is dark, and only the wing with fire escapes is lit and accessible. The eye of providence seems not to know or care about what is inside; in any case, here God is only potentially available upon exit.

This is not to suggest that the show is tragic; indeed, the entire exhibit is a triumph of creativity, defiance, and love. Artists pay tribute to the fallen in painting, video, textiles, and sculpture, remember those who were there, and call out those who refused to be present. Charles LeDrey’s teddy bear in a box from 1991 suggests both mourning and the end of innocence. In Rosalind Solomon’s gelatin silver print “Silence Equals Death, Washington, DC,” 1987-90, a young man covered in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions confronts the camera wearing full protest regalia, including ACT-UP buttons, a straw hat, and a paper Star of David. Frank Moore’s “Patient,” 1997-1998, shows an empty hospital bed painted with leaves and snowflakes, where environmental devastation and AIDS are emergencies that require equally urgent care.

Kia LaBeija’s glossy technicolor photographs, such as “Eleven, October 2015,” and “Kia and Mommy” (below) document her dignity living with hospitals and doctor visits, and celebrate fashion and makeup as creative gestures that make everyday life beautiful.

The pieces gathered here span three-and-a-half decades and include work by people still living, as well as cataloging the talent of too many who died too soon. Their project is a deeply moral one: to remind viewers that sick people are human, that no one deserves to suffer, that death comes for all of us, and that the proper response to tragedy is always—must be—art, compassion, and action.

Jaime Hovey is Associate Program Director for Virtue, Happiness, & the Meaning of Life.

ArtAIDSAmerica Chicago runs through April 2.