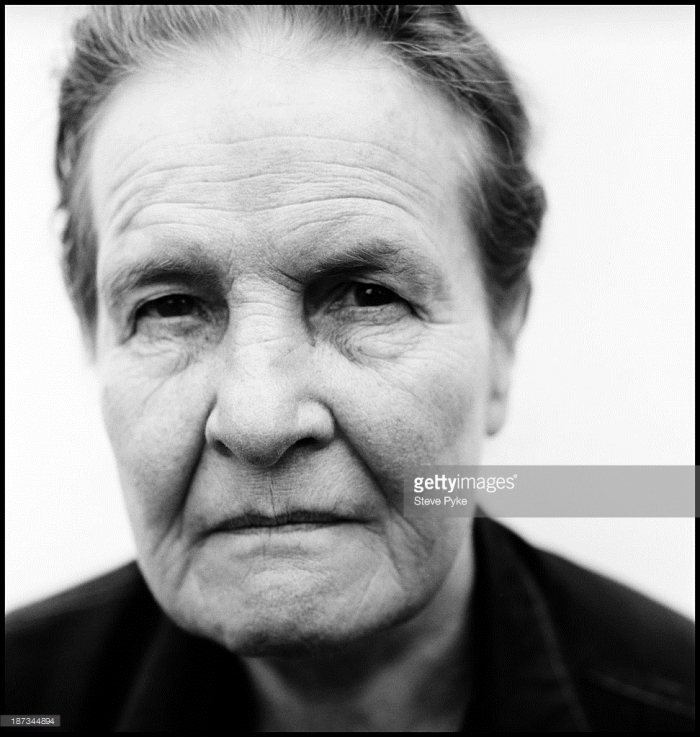

G.E.M. Anscombe (1919-2001) was a British analytic philosopher often credited with initiating the return to the study of the virtues in her famous essay, “Modern Moral Philosophy” and with revitalizing interest in the philosophy of action with her enormously influential monograph, Intention. In this series of posts, we will explore some of her later writings about beliefs and how our epistemic agency might be part of our overall character formation. Note: This is part three of the three part series.

The St Andrews Studies in Philosophy and Public Affairs, a series run under the auspices of the Centre for Ethics, Philosophy, and Public Affairs at the University of St Andrews and overseen by John Haldane, has now published the fourth and final volume of Elizabeth Anscombe’s hitherto uncollected and unpublished papers, Logic, Truth and Meaning: Writings by G.E.M. Anscombe, Edited by Mary Geach and Luke Gormally. For those who have been waiting to see what remains of her Nachlass that has been deemed worthy of publication, this is a significant event. Of special interest in this volume are three essays on beliefs, all of which are undated typescripts. These are “Motives for Beliefs of All Sorts,” “Grounds for Belief,” and “Belief and Thought.” My previous two posts discussed “Motives for Beliefs of All Sorts” and “Grounds for Belief.”

And now we come to the most substantive essay on belief, “Belief and Thought.” It too is unfinished (there is a footnote that references two further sections that have either been lost or that never came to fruition). The essay is mostly taken up with various puzzles about belief and thought that arise as we think through assent and assertion, concepts that are central to the distinction between thinking and believing. Its main contribution, I think, is its attempt to take seriously the separation of the logical and the psychological in an account of belief.

Anscombe notes that belief is a “curious concept” because its grammar seems to shift when we apply the concept in different contexts. Sometimes belief is treated dispositionally, but in other cases it isn’t (cases of suddenly believing something, for instance). It seems wrong to say that there are two equivocal senses of belief, as there are two equivocal senses of bank. Nor does it seem right to say that the non-dispositional use signifies a mental act or state of consciousness, since we fail to find such a thing when we survey our mental lives.

A somewhat traditional understanding of the distinction between mere thought and belief is that belief is what one gets when something is added to a mere thought: a mental act of assent. We are tempted by the view that something needs to be added to thought because thought can be a mere grasping of a sense, and understanding, without endorsing what is thought – without in any sense taking it to be true. Thus we can separate judgeable content, something assertable, and assent to what is assertable. When someone does think that such and such is the case, he has done two things: grasped a judgeable content and inwardly assented to it.

Assent is assertion of what is assertable (perhaps the assertion is only inward). There are two ways we might conceive of this. The first is that it is an extra feature that attaches to thought; the second is that it is intrinsic to the thought unless special circumstances take it away. Let us call the former the additive view and the latter the defeasibility view.

There are many considerations that seem to support the additive view. First, the same judgeable content when placed in an if-then clause is not asserted. Second, one can obey a command to think something as being so without thinking it as so: one says, “think of a man with a horse’s tail” and straightaway I do it. Third, things can just cross my mind, but this in no way implies that I believe them. Fourth, when fictional accounts are brought to the mind I don’t believe that they are true. And so on.

But there are equally many reasons to think that assertion is not something added to thought. First and foremost, there is the fact that when I search around for this inner act of assent, I simply do not find it. And though it is true that thoughts can come before the mind, this is thought understood in its logical and not its psychological sense, and thought in its logical sense can contain within it assertion in its logical sense. Assertion needn’t be some extra, psychological ingredient.

Ultimately, Anscombe rejects both accounts. She writes:

Each seems to involve a myth: the defeasibility theory, that of a sort of content which if it occurs in the mind at all must be being believed, or must be being believed unless there is some explanation why not…; and the other, that of the indescribable addition, the act of assent. Both views must arise from a failure to understand. (163)

I think the failure that Anscombe is pointing to is the failure to see the distinction between logical and psychological accounts of assertion.

The defeasibility theory fails as a psychological theory; it says that we must believe any judgeable content that is present to our minds unless special circumstances can explain our not doing it. But this denies the possibility of entertaining mere ideas. It also has trouble accounting for negation. If ‘p’ is before the mind, then the mind must be assenting to it. But if ~p is before the mind, then so is p, for the negation contains the thought that it negates. But I can’t be assenting to both at the same time. But if we say that the corresponding negative idea is not in the offing, then it is unclear what assent amounts to.

Anscombe thinks it will help us to distinguish between grammatical kinds of assertion – logical and psychological. Assertion might be a personal act of mind, but it might also be “a logical character of the proposition as such” such that it can be the “instrument of personal assertions” (166). But there is still logical unassertedness, such as what falls within an if-then clause – here the propositions are asserted in neither sense. How can we say both that the proposition itself asserts and that it occurs unasserted?

Anscombe’s solution, which she takes from Julianne Mott Rountree, is that assertion is context dependent and that we need to be able to grasp the completeness of a context in order to know whether a proposition is asserted. Skipping over the technical details, assertion is not a matter of adding something or taking it away in specified circumstances; rather, “a proposition in itself is an assertion” but “it is not asserted in every context in which it occurs.” The basic notion here is “assertedness in a context”; if the context is simply the proposition, then it is logically asserted, but if it is placed in a different context, say within an if-then clause, it is not. We can only get there if assertedness is fundamentally contextual. The understanding of the completeness of a context is a kind of skill or knowledge-how, rather than a knowledge that, and this implies that once again this knowledge is justified by one’s mastery of a practice and a set of rules. It is also important to this account that psychological assertion depends upon the logical character of assertedness. She writes:

Personal asserting is something we can do because the tools of assertion – the propositions we can construct in our language – lie ready to our hand, and it is not the personal act of asserting which confers their assertive character on the propositions. (169)

So much, then, for the traditional view of the distinction between thought and belief.

The essay ends with some reflections on Moore’s paradox. Moore thought it was absurd to say “I believe p, but not p” or “p, but I don’t believe that p.” It is tempting to understand the paradox in terms of contradictory assertions, but Anscombe thinks that would be a mistake. First, “I believe p, but perhaps not p” has nothing wrong with it; whereas both “p, but perhaps not p” and “I say that p, but perhaps not p” are objectionable. The absurdity of the paradox is better understood in terms of expressions of beliefs. For p does not occur asserted in “I believe that p” and the problem with assertion drops out. The absurdity is just that one cannot at one and the same time take p to be the case and p not to be the case. Here we see something fundamental about what it is to express a belief – to express that one does so take p. To believe something is indeed to mean to believe it.

This series originally appeared as “The Capacious and Consistent Mind of Elizabeth Anscombe” in International Journal of Philosophical Studies, Vol 24, 2016, Issue 2.

Jennifer A. Frey is a principal investigator with Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life.