These remarks correspond to our latest Virtue Talk podcast with Tahera Qutbuddin, which you can listen to here.

I grew up in Mumbai, India, studied Arabic at Ayn Shams University in Cairo, Egypt, and came to Harvard University in the US for my PhD, which I completed in 1999. After that, I taught for a year at Yale University, then for two years at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. In 2002, I joined the University of Chicago, where I’m currently Associate Professor of Arabic Literature in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations (NELC). At the University of Chicago, I’m also affiliated with the Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES), the Committee on South Asian Studies (COSAS), and the Divinity School. And for the past six years, I’ve chaired a non-traditional major in the College named Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities (IS-Hum).

My work centers on classical Arabic literature. I have a deep interest in literary materials of the early Islamic period that preach virtue, which is my connection with the Virtues group of scholars. Overall, my scholarship focuses on intersections of the literary, the religious, and the political in classical Arabic poetry and prose. My areas of research are classical Arabic oratory and Islamic preaching (khutba); the Quran, traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, and the sermons and sayings of the first Shia imam and fourth Sunni caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib; and Fatimid-Tayyibi history and literature (the Fatimids were a Shia dynasty who ruled North Africa and Egypt from the 10th through the 12th centuries, and the Tayyibis are a Muslim denomination in Yemen and India, who look to the Fatimid legacy). I’ve also worked on Arabic in India.

My first journal article, which I published in 1995 while I was a graduate student at Harvard, was titled “Healing the Soul: Perspectives of Medieval Muslim Writers.” I discussed the ideas of certain key scholars in the Islamic tradition who used the metaphor of the physician and healing to promote virtue and faith. I found that the earliest accounts were based in either Greek ethics or the Qur’an, and the Greek aspects were rendered over three centuries into an Islamic matrix.

In my first monograph—published by Brill in 2005 titled Al-Mu’ayyad al-Shirazi and Fatimid Da’wa Poetry: A Case of Commitment in Classical Arabic Literature—I combined material and approaches from several disciplines to analyze the poetry of the 11th century scholar, al-Muʾayyad al-Shīrāzī, who was chief missionary for the Fatimid caliphs of Egypt. Al-Mu’ayyad is acknowledged as a giant in the Fatimid philosophical tradition, but none had worked on his poetry before. Because it is underpinned by esoteric doctrine, its true significance cannot be decoded without careful perusal of its philosophy and history. I found and used manuscripts of his poetry housed in private collections in India, and I also used an eclectic package of literary, historical, and theological primary sources, many of them also in manuscript form. I argued that al-Muʾayyad flew in the face of the rival Abbasid court’s conventional panegyric to create a new, very personal, “committed” form of Arabic poetry, with themes, imagery, and audiences consonant with his religio-political cause.

My currently ongoing monograph project is tentatively titled Classical Arabic Oratory: Religion, Politics and Orality-Based Aesthetics of Public Address in the Early Islamic World, for which I’m honored to have been awarded fellowships by the Carnegie Corporation and the American Council of Learned Societies. In the 7th and 8th centuries AD, oration was a crucial piece of the Arabian literary landscape, reigning supreme as its preeminent genre of prose. It was an integral component of pre-Islamic and early Islamic leadership, and it also had significant political, military and religious functions. Its themes and aesthetics had enormous influence on subsequent artistic prose. Little has come forth on the subject, due to substantial challenges posed by an archaic lexicon (these are hard texts to crack!), a vast array of sources, and the sticky question of dating. But I believe an approach sensitive to its oral underpinnings can meaningfully delineate key parameters of the genre. I’m analyzing the texts and contexts of these earliest Arabic speeches and sermons, and I hope to construct thereby the first comprehensive theory of classical Arabic oratory.

In the past five years, much of my intellectual energy has been directed to a new publication series titled “Library of Arabic Literature,” and it has been a joy and a privilege to be part of this emerging venture. In 2010, I was invited to its newly-forming Editorial Board, whose mandate is to produce facing-page Arabic editions and English translations of significant works of Arabic literature, with an emphasis on the 7th to 19th centuries, encompassing a wide range of genres, including poetry, religion, philosophy, law, science, and history. The project is supported by a grant from the New York University Abu Dhabi Institute, and its volumes are published by NYU Press. Its Editorial Board comprises a team of Arabic/Islamic professors at educational institutions in the US and UK. We meet twice a year in New York and Abu Dhabi, and in the first five years, we have produced a resounding 35 volumes. In 2015, our grant was renewed for another five years, and in this second phase we aim to bring out an additional 40 volumes.

Many of the really important texts of early Islamic literature remain in manuscript form, and many have not been translated into English, or have been translated in less than lucid renderings. In addition to my analytical research work, I’m also committed to making these masterpieces of Arabic literature available in reliable editions and engaging translations, especially those among them that promote virtue and contemplation.

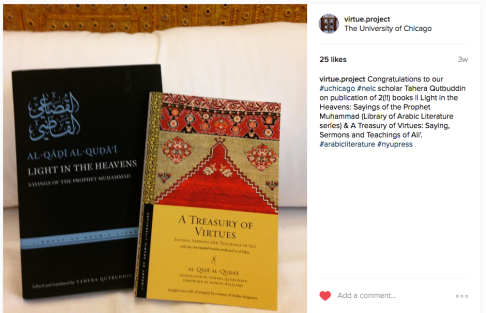

In this context, I edited and translated a volume of Sayings, Sermons, and Teachings of Ali ibn Abi Talib, whom I mentioned before, who was the cousin and son in law of the prophet Muhammad, and the first Shia imam and the fourth Sunni caliph. (Library of Arabic Literature, NYU Press, 2013). The volume was compiled by al-Quda’i, who was a judge in medieval Cairo. The book is titled A Treasury of Virtues, and in beautiful desert metaphors and brilliantly pithy Arabic, it enjoins universal human virtues such as justice, wisdom, and kindness, presenting them in an Islamic and Quranic framework. For example, “ The best words are backed by deeds” “Oppressing the weak is the worst oppression” “Knowledge is a noble legacy” “The true worth of a man is measured by the good he does” “There is no treasure richer than contentment” “A just leader is better than abundant rainfall.”

I’ve recently completed editing and translating another volume for the series, this one being a compilation of the ethical and doctrinal sayings of the prophet Muhammad titled Light in the Heavens, by the same compiler, al-Quda’i. In a happy coincidence, its  release date is today, November 8. The prophet Muḥammad (d. 632) is regarded by Muslims as God’s messenger to humankind. In addition to God’s words—the Qurʾan—which he conveyed over the course of his life as it was revealed to him, Muḥammad’s own words—called hadith—have a very special place in the lives of Muslims. They wield an authority second only to the Qurʾan and are cited by Muslims as testimonial texts in a wide array of religious, scholarly and popular literature—such as liturgy, exegesis, jurisprudence, oration, poetry, linguistics and more. Preachers, politicians and scholars rely on hadith to establish the truth of their positions, and lay people cite them to each other in their daily lives. These hadith disclose the ethos of the earliest period of Islam, the culture and society of 7th century Arabia. Since they also form an integral part of the Muslim psyche, they reveal the values and thinking of the medieval and modern Muslim community. Most importantly, they provide a direct window into the inspired vision of one of the most influential humans in history. These are a few sample hadith from the volume, which list traits that God loves: “God loves gentleness in everything,” “God is beautiful and loves beauty,” “God loves those who beseech him,” “God loves those who are virtuous, humble, and pious,” “God loves the believer who makes an honest living,” “God loves the grieving heart”.

release date is today, November 8. The prophet Muḥammad (d. 632) is regarded by Muslims as God’s messenger to humankind. In addition to God’s words—the Qurʾan—which he conveyed over the course of his life as it was revealed to him, Muḥammad’s own words—called hadith—have a very special place in the lives of Muslims. They wield an authority second only to the Qurʾan and are cited by Muslims as testimonial texts in a wide array of religious, scholarly and popular literature—such as liturgy, exegesis, jurisprudence, oration, poetry, linguistics and more. Preachers, politicians and scholars rely on hadith to establish the truth of their positions, and lay people cite them to each other in their daily lives. These hadith disclose the ethos of the earliest period of Islam, the culture and society of 7th century Arabia. Since they also form an integral part of the Muslim psyche, they reveal the values and thinking of the medieval and modern Muslim community. Most importantly, they provide a direct window into the inspired vision of one of the most influential humans in history. These are a few sample hadith from the volume, which list traits that God loves: “God loves gentleness in everything,” “God is beautiful and loves beauty,” “God loves those who beseech him,” “God loves those who are virtuous, humble, and pious,” “God loves the believer who makes an honest living,” “God loves the grieving heart”.

Among the recent articles I’ve published, some are on Ali’s preaching. In one recent article I examine Ali’s melding of core Islamic teachings of the Quran enjoining piety and good works, with the oral, nature-based cultural ethos of seventh-century Arabia. Another recent article—and this is the one I shared with the Virtue scholars’ group in December—looks at Ali’s contemplations on this world and the hereafter in the context of his life and times. I argue that Ali encourages his followers to enjoy a happy life on earth and be grateful for God’s innumerable blessings, yet always keep preparing for the imminent hereafter, by cultivating virtuous traits and performing virtuous deeds. I’d like to read out to you a short excerpt from one of his sermons from this article:

O you who reproach this world while being so willingly deceived by her deceptions and tricked by her falsehoods! Do you choose to be deceived by her yet censure her? Should you be accusing her, or should she be accusing you?! When did she lure you or deceive? Was it by her destruction of your father and grandfather and great grandfather through decay? Or by her consigning your mother and grandmother and great grandmother to the earth? How carefully did your palms tend them! How tenderly did your hands nurse them! Hoping against hope for a cure, begging physician after physician for a medicament. On that fateful morning, your medicines did not suffice them, your weeping did not help, and your apprehension was of no benefit. Your appeal remained unanswered, and you could not push death away from them although you applied all your strength. By this, the world warned you of your own approaching end. She illustrated by their death your own.

Indeed, this world is a house of truth for whomsoever stays true to her, a house of wellbeing for whomsoever understands her, a house of riches for whomsoever gathers her provisions, a house of counsel for whomsoever takes her advice. She is a mosque for God’s loved ones, a place where God’s angels pray, where God’s revelation alights, where God’s saints transact, earning his mercy and profiting paradise.

In addition to the publications I’ve talked about, I always look to avail of opportunities to reach outside the ivory tower, and have lectured over the years on general topics related to Islamic history and Arabic literature, particularly on topics that promote goodwill among the human family. Two years ago, I gave a talk on “Imam Ali’s Preaching of Peace and Pluralism” at a UNESCO conference in Paris organized by its Iraq office titled “The contribution of Ali ibn Abi Talib’s Thought to a Culture of Peace and Intercultural Dialogue.” Just recently in September of this year I helped organize a conference in Kolkata, India, on exemplars of communal harmony in pre- and post-Independence India, that was hosted jointly by my father’s educational foundation Qutbi Jubilee Scholarship Program (QJSP) and the University of Calcutta, and was attended by the Vice Chancellor of the University of Calcutta, and the West Bengal Minister for Higher Education, and widely covered by the local media.

I’m very pleased to be part of the Templeton Foundation’s project Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life. I’m grateful to the Templeton Foundation for funding it, and to Candace Vogler for inviting me to participate. This has been a wonderful opportunity for me to expand my horizons, and bring my work into conversation with the major Western philosophical and theological traditions. I’ve especially enjoyed the practical perspectives of psychology and economics brought by the social scientists in the group on questions of virtue and happiness. It’s been a privilege to listen to these amazing scholars.

I’ve found many parallels with the classical Islamic traditions I work with, and hope to make use of these new insights and apply them to my own work. For example, many of the group’s scholars work on Thomas Aquinas, and the harmony of faith and reason that is expressed in his teachings resonates with several schools of Islamic thought, especially one that I work with, the Fatimid-Ismaili school. Others work on Aristotle, and his cardinal virtues of justice, temperance, wisdom, and courage are strongly reflected in the early Islamic aphoristic material, and in the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad and Imam Ali. The material my colleagues on the Virtue Scholars team work on is itself fascinating, and the questions and methodologies they bring to bear on it are equally illuminating.

I’m also happy to have the opportunity to present some Islamic approaches to virtue, to these scholars who may not have engaged with the Islamic tradition in any depth before.

A significant prompt that has come out of this workshop for me is a renewed emphasis on the importance of harnessing ideas to promote virtue and happiness on the ground. This is academic work, but it’s also very personal. The research on the hows and whys of a meaningful life discussed at the workshop is really valuable. For me, the natural corollary to the expert analysis is how to translate this information into becoming a better human being myself, and to work toward promoting kindness and virtue in the many communities I’m part of. The research, both individual and collaborative is important. But it’s equally important to think about how to use that practically to be a nice, kind person oneself, and to promote niceness and kindness among the people we live. I’m delighted to be part of this ambitious project, and I hope that together we can make a difference, and offer some contribution to a better and more peaceful world.

Tahera Qutbuddin is Associate Professor of Arabic Literature at the University of Chicago and Scholar with the project Virtue, Happiness, & the Meaning of Life.

Click the link below to hear our scholar and Professor of Arabic Literature Tahera Qutbuddin discuss her research and recent books A Treasury of Virtues: Sayings, Sermons, and Teachings of ‘Ali, and Light in the Heavens: Sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, and how her research is impacted by working within our project.

Click the link below to hear our scholar and Professor of Arabic Literature Tahera Qutbuddin discuss her research and recent books A Treasury of Virtues: Sayings, Sermons, and Teachings of ‘Ali, and Light in the Heavens: Sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, and how her research is impacted by working within our project.